ELAINE GAN

PLEASE SELECT ONE from the index below or scroll →

-

1960 — MIRACLE RICE — ACCELERATION

In the early 1960s, agronomists at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in Los Baños, Philippines began crossfertilizing rice varieties to develop seeds that could deliver the highest crop yields in the shortest amount of time, to feed growing populations in Southeast Asia. Funded by the Rockefeller and Ford foundations in the U.S. and building on wheat and maize research at CIMMYT in Mexico, IRRI introduced "miracle rice", varieties of Oryza sativa with growth and harvest times accelerated by a slew of agricultural inputs. Nitrogen fertilizers pumped into the soil inadvertently produced better habitats for insects called brown planthoppers (BPH), which are vectors for a powerful rice killer called grassy stunt virus.

This chapter attends to the unintended race that emerged between an unlikely assemblage: miracle rice, nitrogen, an insect, and a virus.

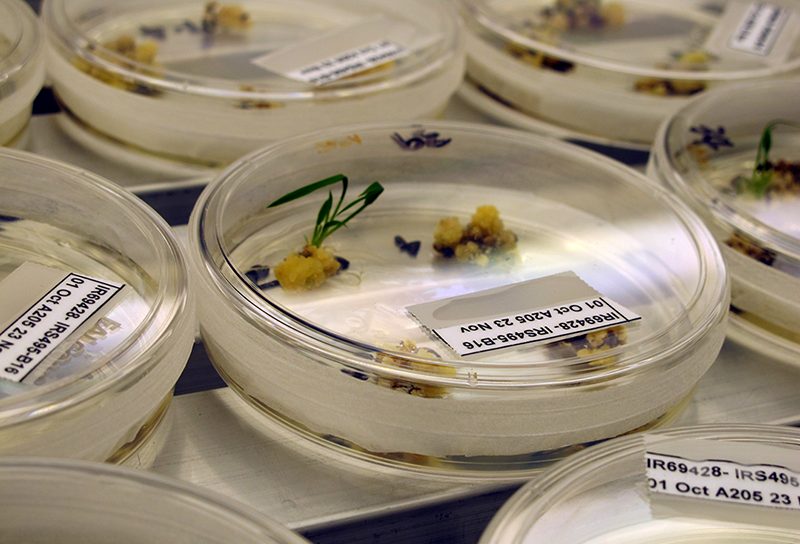

IMAGE: Test varieties of rice being germinated by biologists at IRRI labs in Los Baños (Wanda Acosta, 2010).

-

18th CENTURY — MONSOON — OSCILLATION

Every year, monsoon rains signal the rice planting season and fish migrations along the Mekong, the longest river in Southeast Asia. Flowing through five countries, the river has many names among the 40 million people who depend on it: Cambodian Mékôngk, Laotian Mènam Khong, Thai Mae Nam Khong, Chinese Lancang Jiang or Lan-ts'ang Chiang, Vietnamese Sông Tiên Giang or Cuu Long, the river of Nine Dragons. To be a farmer here is not just to name, but to work rice through seasonal rhythms, monsoon rains and floods, flows of freshwater and saltwater, sedimentations of soil that need constant dredging, and climate oscillations. To work with rice is to coordinate with earth, sky, wind, sea, and rain. Such coordinations have taken millenia.

This chapter looks at the cultivation of long-stemmed floating rice or deepwater rice, the global impact of El Nino events in 1789-1793, the construction of massive hydroelectric dams along the Mekong in recent decades (e.g., Xayaburi in Laos), and the impending extinction of the planet's largest freshwater fish species, Pangasianodon gigas, a giant catfish.

IMAGE: A floating food market, one weekend in the Mekong Delta (Wanda Acosta, 2011).

-

2006 — SEED VAULT — UNDO and FOREVER

Construction of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault began in 2006 on Longyearbyen, a special economic zone of Norway. Funded and managed by the Norwegian government, Global Crop Diversity Trust, and Nordic Genetic Resource Center (NordGen), the vault's mission is to provide a secure backup of seeds for the world's crops.

Tunneled deep into a sandstone mountain, the vault now contains 850,000 seed accessions from various agricultural research institutes and can store up to four million. Seeds are frozen at a temperature of -18 degrees Celsius, allowing them to stay viable for a few hundred years, available for comebacks in the event of human error or environmental catastrophe.

This chapter unpacks the seed vault as a series of nested enclosures made possible by temporal logics of "undo" and "forever."

IMAGE: Entering a cold storage room at the seed vault in Svalbard with a NordGen representative (Elaine Gan, 2015).

-

HOLOCENE — WILD RICE — DORMANCY

Archaeologists trace the domestication of plants and animals back 12,000 years, a shift from hunting-gathering to farming that defines the geological epoch known today as the Holocene. This chapter looks at Oryza rufipogon, a wild perennial that is a progenitor of miracle rice. While extremely mobile as seed, rice is largely immobile as a growing plant and relies on coordination to survive. O. rufipogon exhibits dormancy; its seeds can stay viable underground for up to several years. Variable capacities for dormancy maintain a diverse supply of seeds in the soil which can germinate in subsequent cycles. In contrast, miracle rice and commercial varieties today are engineered to lose their dormancy, to germinate as scheduled by humans.

This chapter looks at dormancy through science studies scholar Donna Haraway's notion of play, or nonmimetic attunement.

IMAGE: Illustration of a seed from agricultural economist D.H. Grist's Rice, a survey of cultivation practices around the world, first published in 1953.

-

1637 — BLAST FUNGUS — INVASION

Blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae affects a wide variety of grasses, including rice, wheat, barley, and millet. Fungal spores attach to a plant's leaves, generating enough pressure to rupture the leaf cuticle and invade underlying tissue. From resulting leaf lesions, the fungus sporulates, spreading to other plants. When it infects young rice seedlings, the whole plant dies; infection of older plants results in loss of grain. Every year, this fungal pathogen wipes out up to 30% of rice yield, enough to feed sixty million people.

This chapter follows fungal invasion: first reports of rice blast appeared in China in 1637; in 1704, imochi-byo was reported in Japan; in 1828, brusone appears in Italy; by 1876, it arrives in the United States and soon, to rice-growing regions in over 85 countries. I explore how the spread may work in tandem with shipping networks.

-

WORLD WAR II — CORDILLERAS — RECURSION

Anthropologist-to-be Harold Conklin arrived in the Philippines in 1944. Having joined the army, he arrived at the cusp of an historical turn, when the Philippines shifts from being a U.S. commonwealth to an independent republic. His dissertation in 1954, Hanunoo Agriculture in Relation to the Plant World, as well as his Ethnographic Atlas of Ifugao (1980) opened up a new field of ethnobotany.

This chapter reads Conklin's lifelong studies of coordination across three main axes: social time, landscape, and technology. I look specifically at his mix of tools – ethnography, cartography, and aerial photography – as recursive practices of meticulous description. Rock, soil, water, wind, rain, woodlots, grasslands, swidden, pond fields, and other companions of rice, take part in enacting visually distinguishable and persistent synchronies.

IMAGE: Walking along terraced pond fields in Banaue on New Year's day (Elaine Gan, 2010).

-

1873 — PATENTS — CURRENCY

In 1873, the first patent on a living organism was awarded to Louis Pasteur. U.S. Patent #141,072 described the use of yeast in beer fermentation. In 1875, Jacob Christian Jacobsen, an admirer of Pasteur, established the Carlsberg Laboratory in Copenhagen. This chapter explores the tangled histories of natures and cultures that lead to the possibility of Monsanto seed patents. It traces a cognitive shift that begins to take hold when organisms become technologies that may be commodified through patents and eventually, data algorithms.

-

FOURTH YEAR IN A ROW — DROUGHT — ASYNCHRONY

Drought hangs over California for the fourth year in a row. Farmers pump up groundwater to sustain wilting crops. Housing and development officials introduce new standards for more efficient water use. Photographs of cracked earth show us what the end of the world might look like, recalling Eugene Atget's photographs of Paris a century ago which Walter Benjamin famously described as evidence for scenes of a crime. What is the crime, in the case of drought?

This chapter looks at the Rice Experiment Station at Biggs in northern California, a cooperative of farmers that celebrated its 100-year anniversary in 2012. California rice gathers the flow of snowpack from the Sierra Nevadas, John Deere steel plows, GPS leveling of terraced rice fields, asynchronous rice flowering, the water weevil, and bird migrations.

IMAGE: Bird migrations at Sacramento Wildlife Refuge (Amit Patel, 2011).